A World of Walls

REMEMBERING THE MEDICINE OF A HAND-BUILT WALL

Nikiforos and I are wall-lovers.

Wherever we go, we learn an astonishing amount about a place simply by paying attention to its walls. Not the postcard landmarks, not the curated experiences—but the actual built skin of everyday life. What materials are used? What has been preserved, repaired, or left to weather? What has been hastily replaced, and what has been lovingly maintained?

If you look through our photo archives, you’ll notice something peculiar: there are far more buildings than people.

We’re drawn to buildings like bees to blossoms. We always take note of the way plaster ages and peels, revealing earlier layers beneath—each one a quiet timestamp of human presence. We linger over hand-carved door handles polished smooth by generations of use, the precise way stones are cut and fit together, the color and grit of mortar, the way roof beams push outward to form a protective lip around a structure. Every detail feels like a sentence in a language we’re still learning to read.

Walls tell stories.

They speak of climate and economy, of available materials and inherited skills, of what a culture values and what it has been forced to abandon. They also speak of scale—whether a place was built for human bodies and daily rhythms, or for efficiency, profit, and machines.

A Childhood Obsession

At six years old, I decided I wanted to be an architect. It started in first grade, when on a bring-your-dad-to-work-day, one tall, lanky dad walked up to the black board and introduced himself as an architect.

We spent the morning designing our ‘dream house’ while he drew our ideas on the board as one coherent house (slide from attic into basement pool included).

At some point in the process, I looked around the classroom and realized that every building I’d ever walked through had a person like this lanky dad who had once simply imagined it in their head before bringing it to life. It seemed god-like to me, this ability to dream up lines, shapes, and colors and then see those elements rise up into a living structure before your eyes.

So from that day forward, I wanted nothing more than to be an architect. Yet that dream, at least professionally, quietly dissolved in high school when I realized how much math was involved, and how little joy I found in it. Reluctantly, I let the idea go.

But my love for building never left.

I studied all sorts of place-making schools of thought, just for fun. I bought huge catalogues from Home Depot with 1001 home blueprints, and I browsed them at night before bed like fairy tales, closing my eyes and really imagining how my body would feel sleeping in that bedroom or turning the corner down that hall. I read Frank Lloyd Wright interviews. I drew hundreds of floor plans and homes—for myself, my family, my friends, even my imaginary horses. I built secret huts in the woods behind my house. Whenever my mom’s work took her to some of the nicest properties in our area, I always tagged along. Even today I can still draw an accurate layout of some of those homes, that I had visited just once.

For me, place-making equalled meaning-making.

I understood that a beloved, beautiful container—a home, a horse stable, a school, a hospital, a bus stop—was like the right witch’s cauldron: an alchemical vessel for healing, loving, learning, connection, and transformation.

And I sensed in my young body that spaces built without regard for human scale had a subtle but devastating effect on the people inside them. Buildings designed primarily for industrial convenience quietly instruct us about our value, our role, our usefulness. And if we don’t actively resist, the machine-built world can make us feel more like machines ourselves.

But somehow, over time and despite my best efforts, I’d allowed myself to become more machine-like in my thinking and approach to buildings, the further I got from my childhood.

One Book Changed Everything

One of the most profound revivals of my inner child/architect happened just before my senior year of university in New York City.

I was about to return to the US after a year abroad in Greece, and I knew—viscerally—that my life would draw me back there.

I longed for Greek soil and sea more than I cared for the high honors diploma soon to be in my hands.

Yet the only question was: when?

So, one late summer afternoon in 2007—back in the days before smartphones and back-pocket internet access—I was sitting in an internet café in Thessaloniki, researching how an unskilled gal like me could ever build an abode of her own.

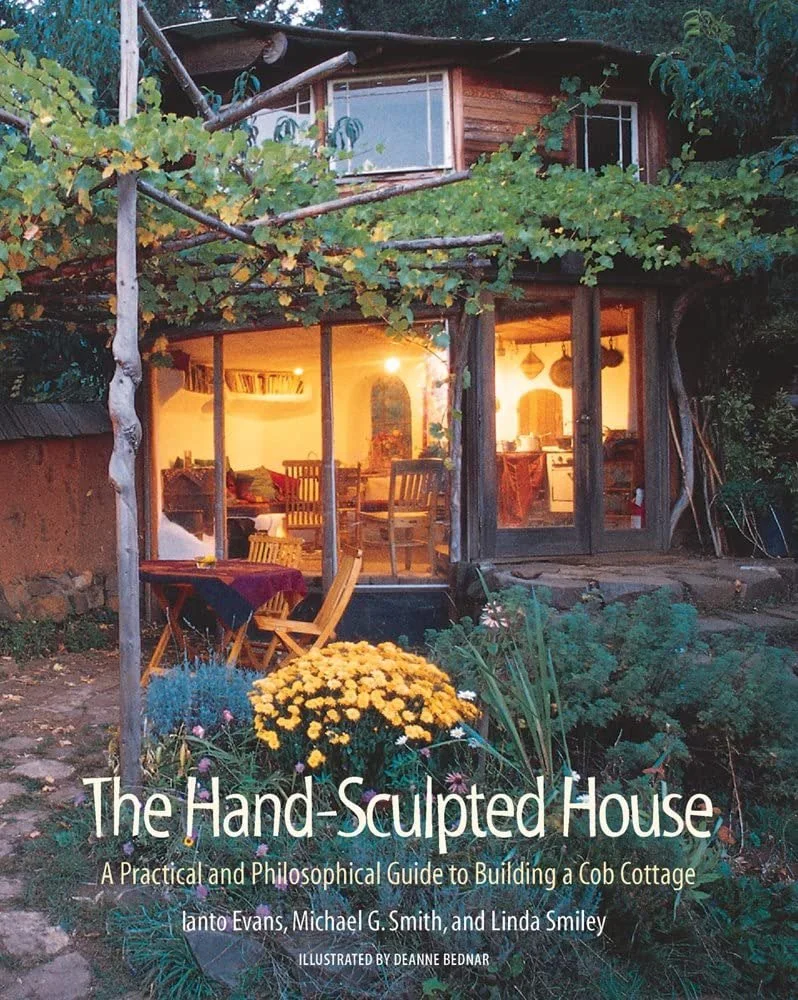

While casually browsing building forums, I stumbled upon a post that mentioned a book that would change the course of my life: The Hand-Sculpted House by Ianto Evans, Michael Smith, and Linda Smiley.

The cover alone stopped me cold.

It’s rustic cabin spoke directly to some locked-away part of me:

Hey—you. Yes, you! You can build your own sacred, magical nook, just like this. You can do it cheaply. You can do it with… mud.

Mud.

Mud?

MUD?!

It’s hard to convey how revolutionary that realization was.

As a suburban New Jersey girl, I’d slowly inherited the idea that building was near impossible, expensive, left to the experts, requiring heavy equipment, hard-hats, and an architect like that lanky dad.

Yet in a matter of seconds, as my body began to integrate what I was reading about MUD, I felt something irrevocably shift. It felt so natural, so obvious, so accessible, so real and healing.

And—dirt cheap.

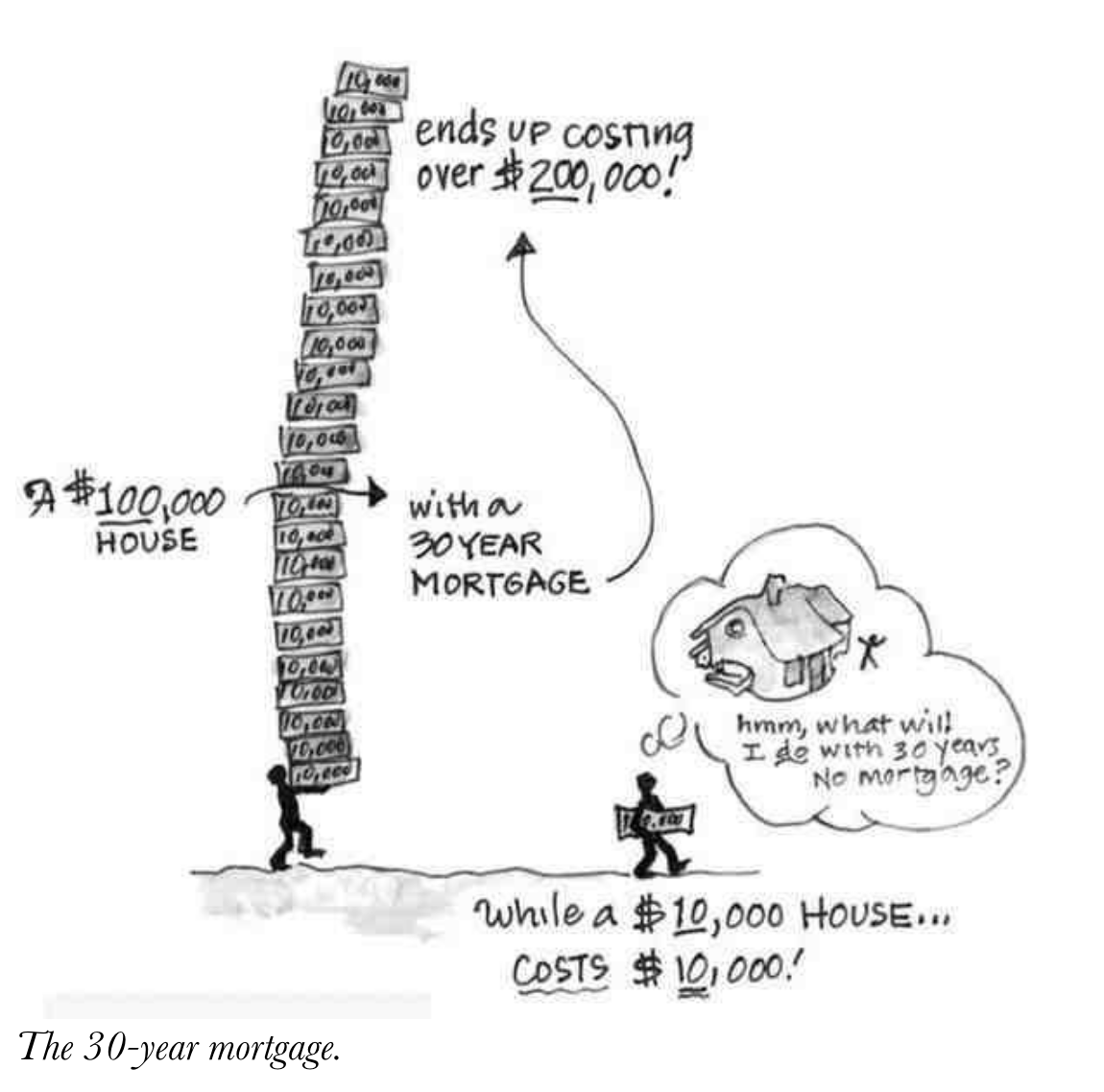

Illustration by Deanne Bedner

Cob wasn’t just a building technique—it was an invitation to a freer way to life.

The book was a clear exit ramp from the conventional path of desk jobs and large mortgages, and an entry into something far more personal, spontaneous, and alive.

And, well—I took that path.

I wrote a passionate letter to Ianto Evans to become his apprentice, and after putting me through rings of fire, he accepted.

Rewilding the Builder Within

My summer apprenticing with Ianto Evans in 2009 deserves a post of its own. But what I can say for now is that the experience re-wilded me. It taught me that the mind alone doesn’t solve anything. Real solutions emerge when you listen to the body’s intelligence, engage your imagination, and awaken your own problem-solving instincts.

These are subtle skills—ones that tend to atrophy in consumerist culture, where dependence on systems is normalized, everything is pre-planned, and little consideration is given to life as it’s actually lived on the ground. Real life is messy. It’s unpredictable. And building—like living—requires responsiveness, humility, and trust.

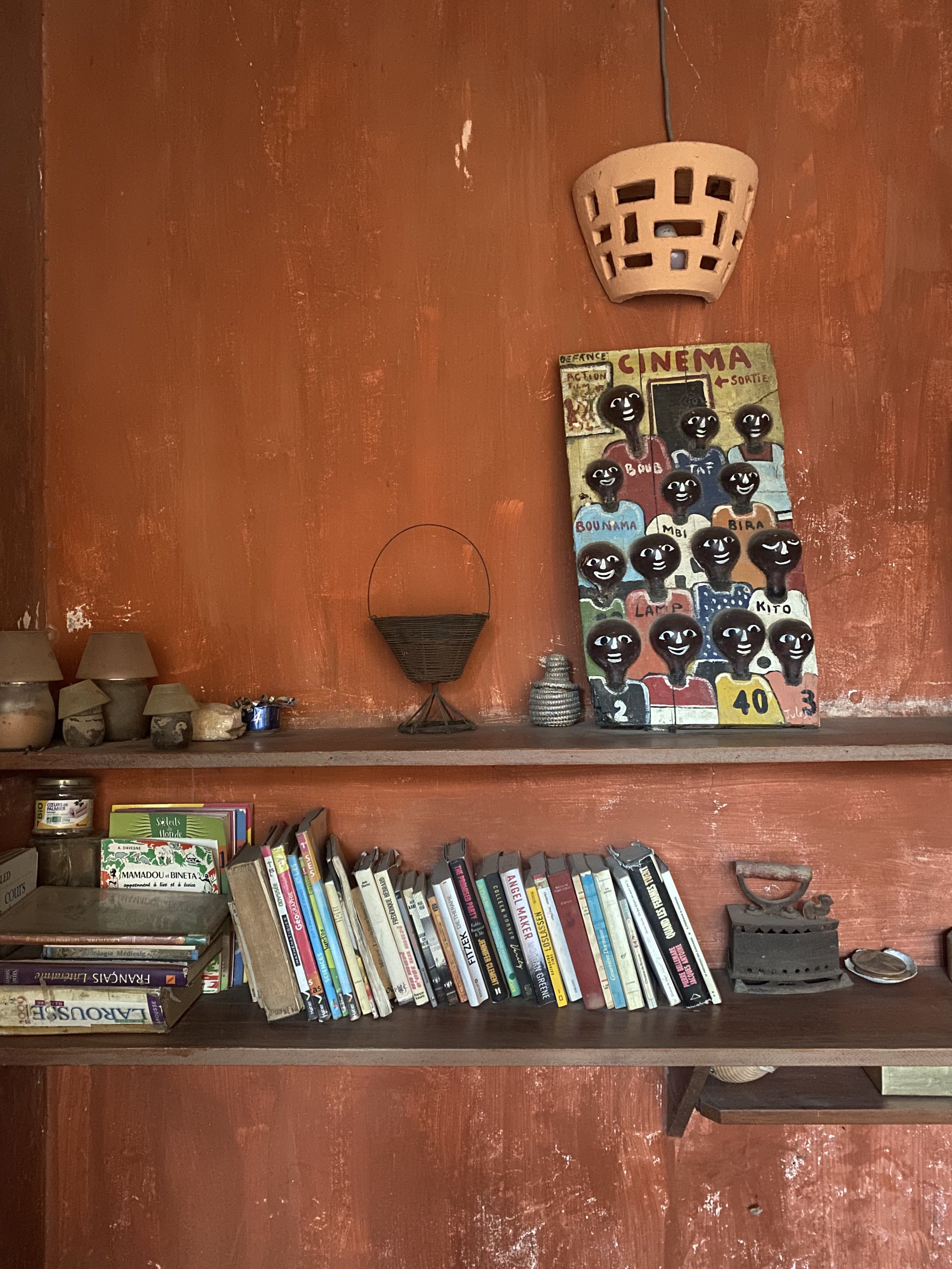

A quiet evening at home, listening to the woods

The Yurt-Cob Nest

A few years later, in 2011, Nikiforos and I decided to put our Greek life on hold and move to my family’s farm outside Princeton, New Jersey. There, we chose to build an experimental home.

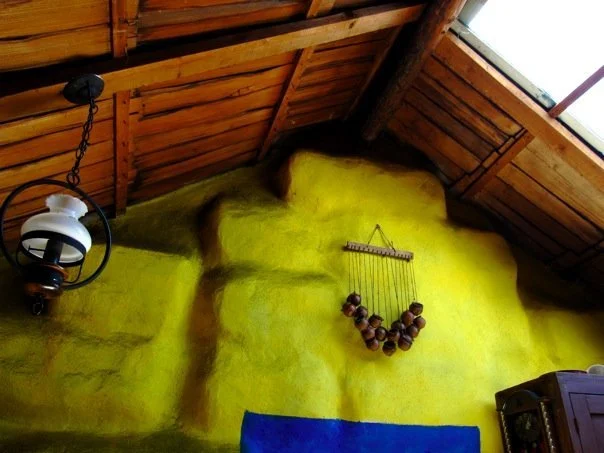

We started with a building-code-approved yurt kit and then dressed it in layers of experimentation and love: interior cob walls, refurbished schoolhouse brick, earthen plasters, even strawbale furniture.

For heat, we used a simple pellet stove—but we also embedded hot-water piping into the earthen walls, connected to an outdoor wood-burning furnace. Whenever the temperature dropped, we’d open a valve and let piping-hot water snake through the walls, warming the space from the inside out through radiant heat. It worked beautifully.

We lived through several brutally cold, snowy winters there, and as long as the stove was running, it was hands-down the most comfortable place to be. (Showering, admittedly, was another story.)

For the earthen plaster on the yurt’s lattice walls, we collected vineyard trimmings from nearby fields, using them as a kind of organic netting to support thick layers of plaster. This added insulation, texture, and a sense of place. And because the yurt is circular by nature, it’s inherently wind-resistant—no sharp corners for drafts or cold spots to gather.

Living Inside the Sky

Living in our yurt was one of the most memorable chapters of our lives. It slowed us down. It tuned us back into nature’s rhythms. It brought us closer to one another.

Through the central skylight, we tracked the arc of the sun across the seasons, and the moon as well. From the loft, we watched autumn leaves change color in the mornings. At night, we fell asleep to stars and snowfall, to owls and coyotes and at dawn in the spring, a chorus of birds happily woke us up. We watched storms arrive, felt them pass through us, and learned what it meant to live with the weather rather than sealed off from it.

It was simple living. And it was magic.

Carrying the Lessons Forward

We’ve carried as many of those natural building lessons as we could with us to Tinos, as we’ve been working through our different renovation projects here, though admittedly every place has its own conversation with nature, materials, and time.

Renovating old stone homes is a slightly different language and lexicon, one we’re still learning from every day.

And we feel blessed to have spent seven years living alongside that beautiful yurt-cob nest.

Walls, after all, are never just walls. They are memory, intention, shelter, and story—quietly shaping who we become inside them.

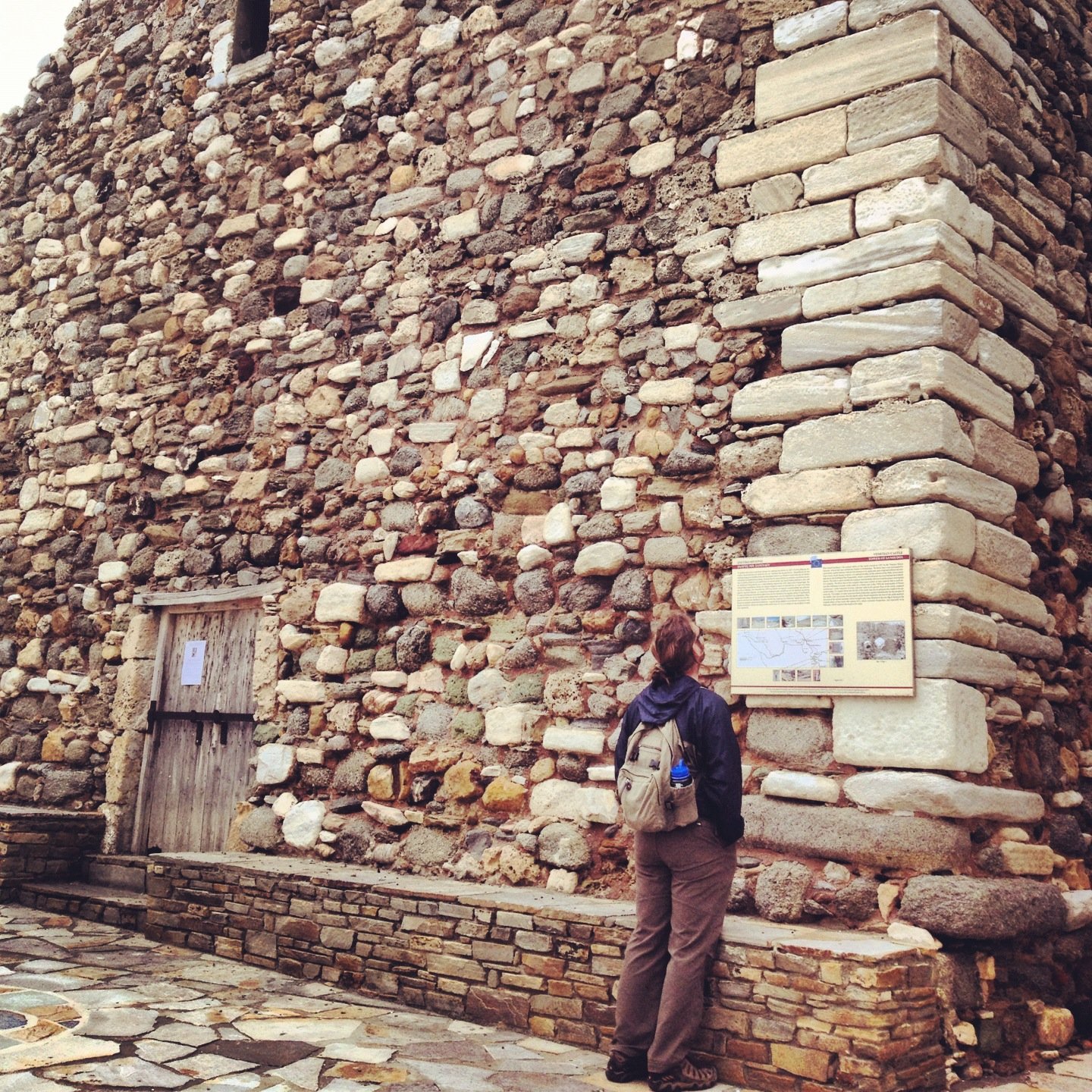

Peruvian earthen wall

Huh? What’s Cob?

Cob is one of humanity’s oldest and most intuitive building methods—a form of earthen construction that uses locally available materials to create thick, sculptural, load-bearing walls built entirely by hand.

Rather than assembling blocks or panels, cob walls are formed as a single continuous mass, allowing builders to shape curves, niches, benches, and shelves directly into the structure.

When properly designed with a raised foundation and generous roof overhangs, cob buildings are remarkably durable, fire-resistant, non-toxic, and capable of lasting for centuries.

At its simplest, cob is made from just a few ingredients:

clay-rich subsoil (the binder)

sand (for strength),

straw or other natural fibers (for tensile reinforcement)

water

The exact proportions depend on the local soil, but the goal is a stiff, dough-like mixture that can be stacked in layers and allowed to firm up gradually as the walls rise. This slow, hands-on process creates walls with high thermal mass, meaning they absorb heat during the day and release it slowly over time, contributing to a stable and comfortable indoor climate.

Historically, cob was a widespread vernacular building method across Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of the Americas, long before industrial materials became dominant.

In places like England, cob homes dating back hundreds of years are still lived in today.

While it fell out of favor during the industrial era, cob has seen a quiet revival as people seek more ecological, place-based ways of building.

More than just a technique, cob reflects a different relationship to shelter—one rooted in local materials, human scale, and an intimate connection between people, land, and home.